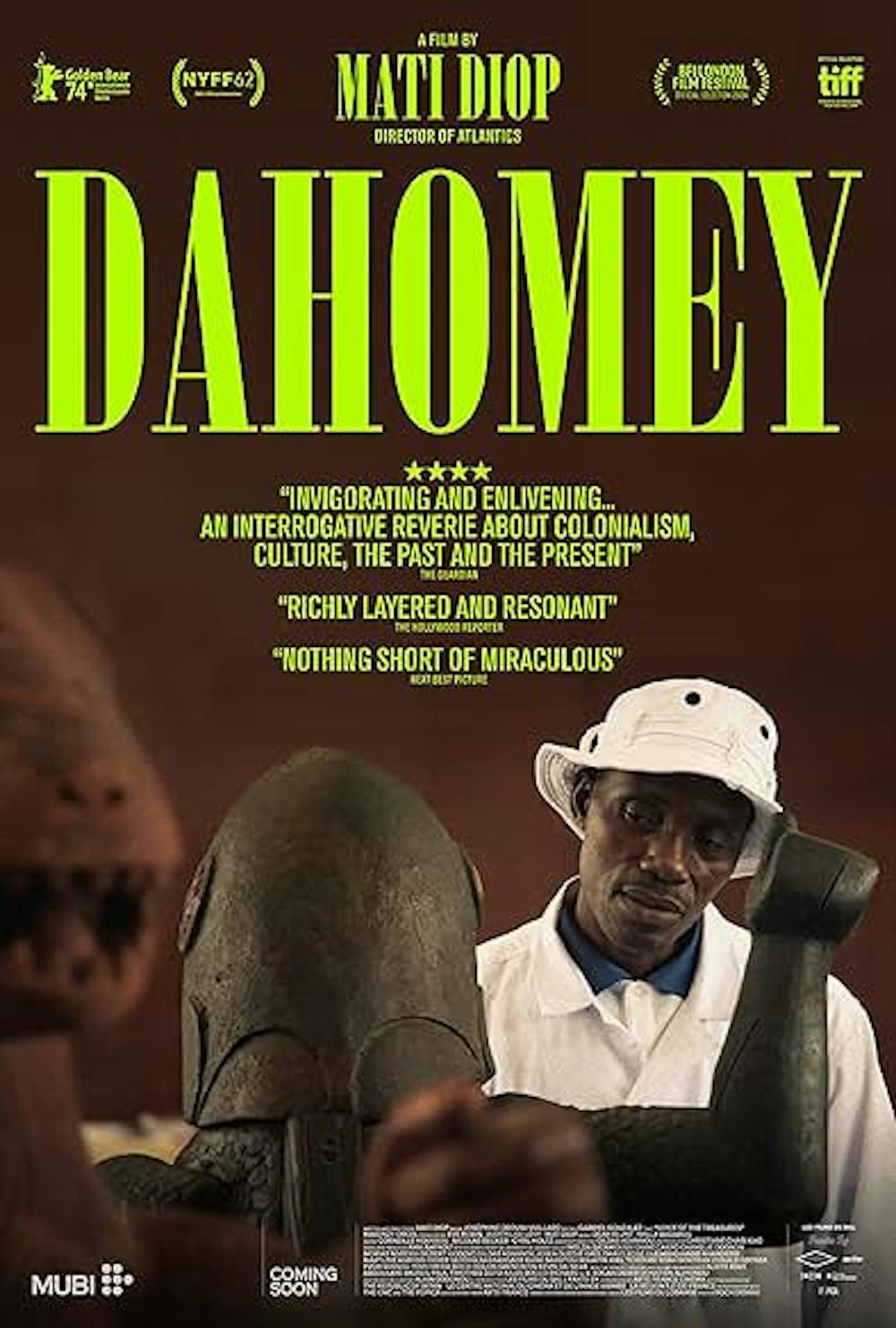

From Feb. 7-10, Albuquerque’s Guild Cinema screened the new documentary “Dahomey.” Directed by French-Senegalese filmmaker Mati Diop, the film follows the journey of a group of artifacts as they are returned from a French museum to their place of origin — the Republic of Benin in West Africa, where the area comprising the former Kingdom of Dahomey is located.

The Kingdom of Dahomey was under French colonial rule from 1894-1960, according to Black History Month 2025. It was during this period that the artifacts in question were looted from Dahomey and taken to France. Prior to their repatriation to Benin, the pieces were on display at the Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris.

According to the museum’s website, its collection contains “almost 370,000 works originating in Africa, the Near East, Asia, Oceania and the Americas which illustrate the richness and cultural diversity of the non-European civilizations from the Neolithic period (+/- 10,000 B.C.) to the 20th century.”

In 2021, Benin reacquired 26 looted artifacts, but that number is only the tip of the iceberg; over 7,000 pieces from the Kingdom of Dahomey were stolen under French rule, according to Point of View Magazine.

“Dahomey” is unlike the vast majority of documentaries. There are no interviews with experts on the subject or firsthand accounts. It’s hardly even a traditional narrative, in the sense that there isn’t any palpable tension or a sense of momentum pushing the story forward. Diop doesn’t have to rely on typical storytelling techniques because she recognizes the most important aspect of making a documentary: observation.

The film is just over an hour long, and Diop makes the most of every second. Such a dense, extensive subject matter could easily warrant an entire documentary series covering it. Making a feature-length documentary that is barely an hour in length is quite a risk, but Diop pulls it off thanks to her calm and self-assured directorial style.

“Dahomey” is slow, yet riveting. Diop is confident in the thought-provoking nature of the documentary’s content, allowing her camera to meander through the journey.

The narrative begins in Paris as the 26 artifacts are being prepared for transportation to Benin. The camera lurks through the hallways and storage facilities of the Musée du quai Branly, observing the sterility of the modern museum — especially one that is built upon the pillaging and colonization of the same countries whose arts and cultures it is now trying to uplift and display.

In a stroke of creative genius, Diop lends voices to the artifacts. By allowing the relics to tell their own stories and histories, they are able to reclaim their culture from the French.

While this storytelling device isn’t typical of a documentary due to its speculative nature, it’s a more effective way of presenting the information than through impersonal interviews or dry narration. The artifacts have personalities and feelings that are distinctly their own, free of European influence.

Much of the film focuses on the 26th statue, which depicts King Ghezo, who ruled Dahomey during the 19th century. He voices his bewilderment at the fact that he was chosen over thousands of his countrymen to return to his homeland. Ghezo refers to his time in France as imprisonment, and shares that he “did not expect to see daylight again.”

The latter half of “Dahomey” depicts how the artifacts are received upon arriving in Benin. They are displayed in a museum in Abomey, the former royal city. Diop observes many generations of Beninese people as they visit the museum, capturing their reactions upon seeing such critical aspects of their culture and history in person for the first time.

Get content from The Daily Lobo delivered to your inbox

A group of students from the University of Abomey-Calavi holds a conference to discuss the impact the repatriation of the artifacts will have on them as young people in present-day Benin. Many students say it’s insulting that only 26 relics out of over 7,000 were reacquired by the Beninese government, while others argue that the repatriation process has to begin somewhere.

Some of the students believe their heritage was lost upon colonization and is only coming back upon the return of the artifacts. On the other hand, some say major components of cultural heritage are the immaterial things, such as dance, music, recipes and ways of life. Through the spirited discussions captured in the film, it becomes clear that there is no one right answer to this long-standing issue.

“Dahomey” is a fascinating, rewarding film unlike any other — one that serves as a crucial reminder that countless societies across the world are still grappling with the effects of colonialism.

Elijah Ritch is a freelance reporter for the Daily Lobo. They can be reached at culture@dailylobo.com or on X @dailylobo