By Elijah Ritch

When I heard that David Lynch died, I simply froze, mouth agape, and stared at the wall for upwards of ten minutes. Obviously he was getting older, and he’d made his battle with emphysema — a chronic lung disease — public in 2024 but he was somebody I imagined would always be with us.

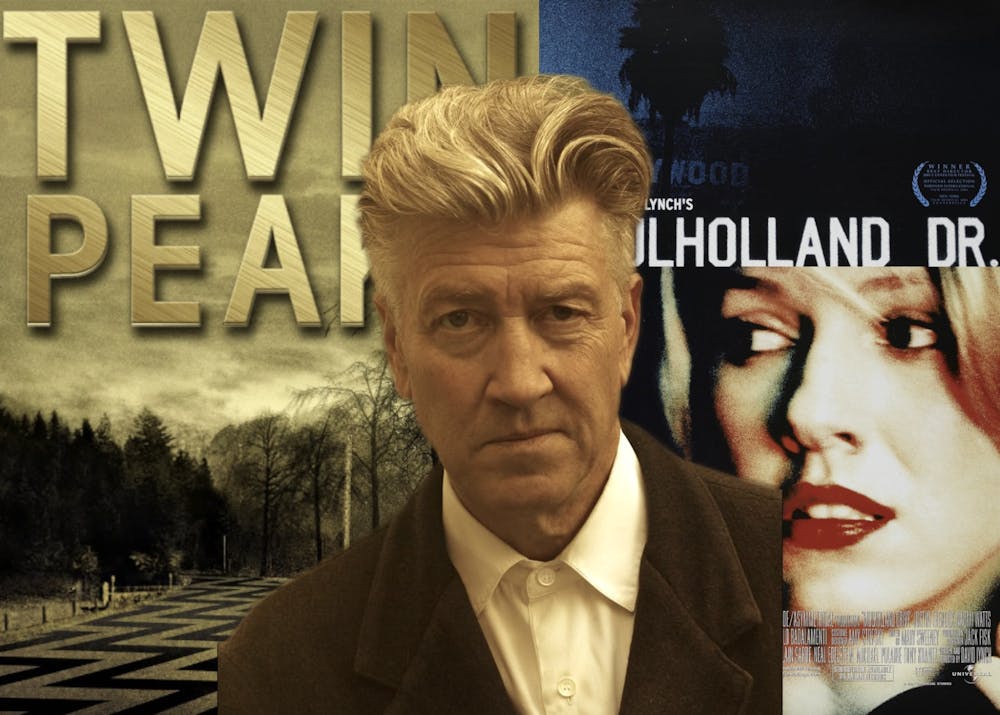

I’m hard-pressed to think of another filmmaker of the past 50 years as influential on both the medium as a whole and specific aesthetic and narrative techniques as Lynch. He has quite literally changed how people both view and make movies. The word “Lynchian” has become commonplace in promotional material and reviews for films with the slightest modicum of surrealism, to the point where the term is devoid of meaning.

In the early decades of cinema, films were seen as an escape into another world, but as the art form evolved, that magic was lost. But Lynch understood the innate magic of the movies. His films feel like transmissions straight from the subconscious while being highly grounded in reality.

I was first exposed to Lynch as a young teenager, when my dad showed me his 1980 film “The Elephant Man.” I was immediately awestruck by Lynch’s ability to find beauty in people and scenarios that others would normally be repulsed by. He understood that the beautiful and the grotesque are inherently intertwined, as are sex and violence.

Over the next several years, I delved further into Lynch’s world. I rarely “got” one of his works upon my first watch. I deeply enjoyed films like “Eraserhead” or “Mulholland Drive” when I originally saw them, but I didn’t know what to make of them. However, as time passed and I was able to sit with specific works, they revealed themselves to me.

His films remind me of the fact that moviegoing is an intrinsically communal experience. In order to truly grasp his work, you have to watch and discuss it with other people. Seeing “Lost Highway” during its theatrical rerelease, viewing “Mulholland Drive” in a film history class and rewatching “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me” with a friend a few days after Lynch’s passing have each allowed me to understand these films in a new light.

I can only hope that Lynch’s passing will inspire established fans to revisit his work and those who are unfamiliar with him to experience the work of a true genius — a man who possessed a once-in-a-lifetime artistic vision.

Elijah Ritch is a freelance reporter for the Daily Lobo. They can be reached at culture@dailylobo.com or on X @dailylobo

By Lily Alexander

“Twin Peaks” changed the way I think about femininity and death alike.

I first watched it in eighth grade — arguably too young to understand the intricacies, but very into the color pallet and Audrey Horne’s outfits. I rewatched it a year ago, staying up late after editing or doing homework, eyes glued to the television screen. I didn’t want to blink; I feared I’d miss something crucial in the chevron floors and perpetual fog.

Get content from The Daily Lobo delivered to your inbox

It’s rare that a male creator develops a tragic female character who feels authentic. There seems to be a popular concern in sci-fi and horror with ensuring women are saveable — often by men. This isn’t always wrong, but it’s not realistic.

Tragedy is a part of life. Sometimes, there aren’t happy endings.

Seventeen-year-old Laura Palmer is the main character of “Twin Peaks,” but she’s dead before the show begins. Lynch and cocreator Mark Frost weave her life into the storyline through the reminiscences of her family, friends and enemies. The audience sees how everyone in Laura’s life viewed her, and ultimately, failed her.

Lynch’s decision to direct a prequel film to the show a year after it originally ended was nothing short of brilliant. “Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me” provides Laura’s side of her story. Lynch gives Laura a voice, highlighting the contrast between the person other people saw and the person she really was.

“Twin Peaks” is a tale of aliens and demons and things that go bump in the night, but “Fire Walk with Me” more patently exposes the plain truths: Laura was a child who ended up in horrific situations and had no place to go because home wasn’t safe. She needed help. No one provided it.

I think of Laura — doomed by the narrative, a ghost and a girl — when I think about the way women deal with pain. Laura put on lipstick and high heels and no one saw through the mask. Can’t we all relate to that in some way?

The other characters and subplots of “Twin Peaks” are entertaining and heavy and genius. Lynch writes people who are strange and sympathetic, tropey and unique. He subverts every norm.

Thank you, David. Love makes the world go ‘round.

Lily Alexander is the editor-in-chief of the Daily Lobo. She can be reached at editorinchief@dailylobo.com or on X @llilyalexander

Lily Alexander is the 2024-2025 Editor of the Daily Lobo. She can be reached at editorinchief@dailylobo.com or on Twitter @llilyalexander