I will be the first to admit I grew up confused by the New Mexican identity because it is a mixture of so many different heritages and experiences. Trying to understand myself and my community through the lens of a Mexican American from southern New Mexico feels like a full-time job.

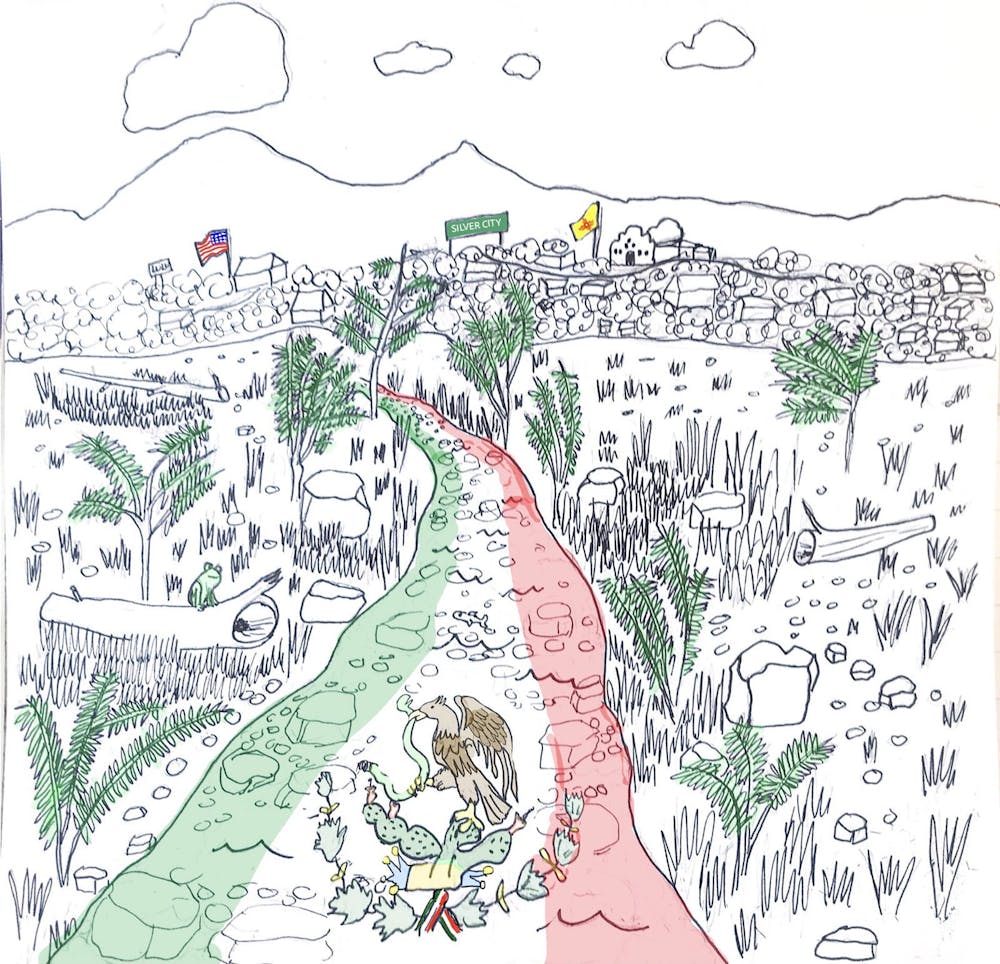

I grew up in Silver City, New Mexico, in a very proud Mexican/Midwestern household. My siblings and I were lucky that we were never told to deny our heritage. While I was allowed to be proud of my Mexican heritage, this was in part because I am also white and don’t have racist views directed toward me. Not everyone has that privilege.

I believed during my childhood that New Mexican culture was defined by a superiority toward those who did not have or claim Spanish blood because of the constant denial of Mexican influence in creating New Mexican culture.

Growing up in the south with little interaction with Northerners, I thought this denial was all there was, and the northerners I knew held this belief to varying degrees. I did not have enough familiarity with New Mexican culture to know any different.

I knew people who vehemently denied being Mexican despite their heritage. Some of them felt more connected to a New Mexican identity. There were others, though, who viewed having Mexican heritage as shameful.

I once had a history teacher who told me that Mexicans were the result of the mixing of Spanish and Indigenous bloodlines. Not New Mexican, but Mexican. These ideas are not new.

To be clear, the Indigenous peoples of Mexico existed long before the conquistadors came. They and their mixed descendants continue to fight for their culture and rights. Oaxaca Ingobernable, an exhibit in the Hibben Center, showcases resistance art by Indigenous and Black Oaxacan communities in Mexico and the United States.

One of my favorite pieces published in “Limina: UNM Nonfiction Review,” titled “I Was Not Touched from the Waist Down,” was published in 2002 and details the struggles within New Mexican culture and labels. The piece investigates the discourse around the theft of a statue of La Conquistadora, which is the title for an aspect of the Virgin Mary in some parts of Santa Fe and northern New Mexico.

As I read the piece, I noticed a difference between southwestern New Mexico Mexican American perceptions and northern Hispanic perceptions of the Virgin Mary. I grew up with stories about how she appeared to Mexican Indigenous people like Cuauhtlatoatzin — or Juan Diego — to show love and encouragement, which made her feel much less like a conquering presence.

When I moved to Albuquerque for college, I met many New Mexicans from all around the state. I met people with varying amounts of Mexican, Indigenous and Spanish heritage who had created a beautiful culture. These new friends were a part of a culture that did not demean the populations with Indigenous and Mexican heritage.

I learned that things my Mexican American family does are occasionally more New Mexican than strictly Mexican. I found joy in the community made up of people who share heritage and live in New Mexico, and not once was I made to feel ashamed of my personal history.

My newfound joy was only possible through a decolonialized attitude. Community is so important in everything we do. As a community, we need to fight against superiority and embrace a commitment to culture and understanding and working for decolonization.

Get content from The Daily Lobo delivered to your inbox

Marcela Johnson is a senior reporter for the Daily Lobo. She can be reached at news@dailylobo.com or on X @dailylobo

Marcela Johnson is a beat reporter for the Daily Lobo, and the editor-in-chief of Limina: UNM Nonfiction Review.