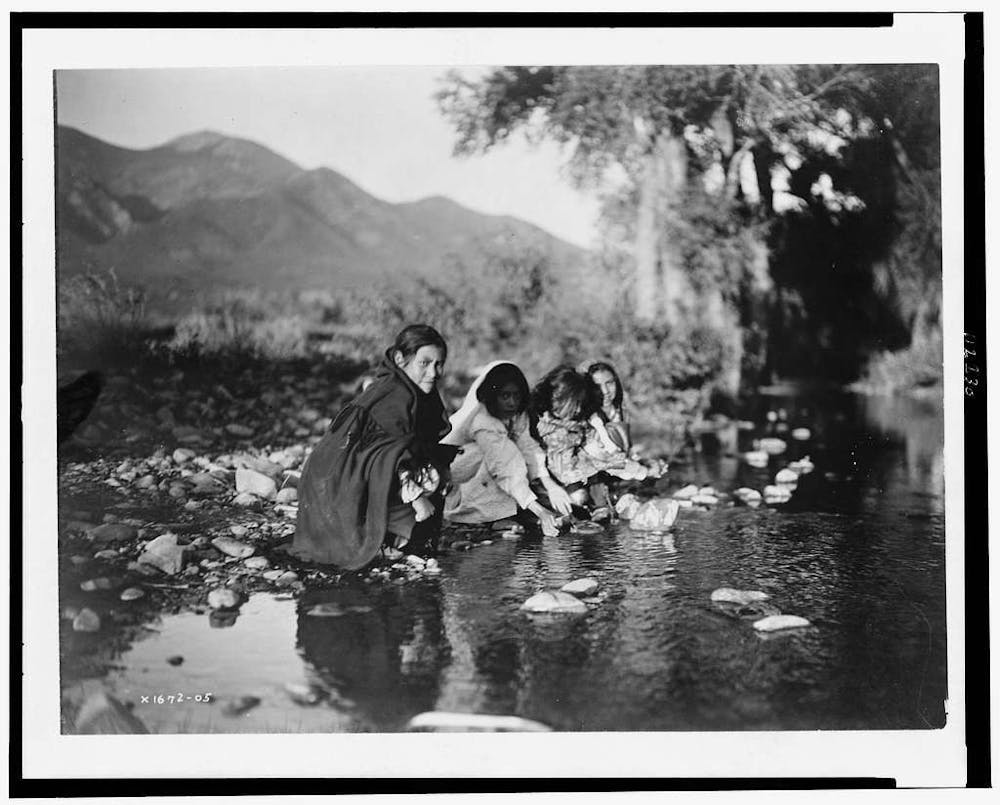

The crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous People has gained attention in recent years. However, it is not new. Violence against Indigenous women dates back 500 years to the start of European colonization, according to a study by A. Skylar Joseph published in the “Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine.”

European colonists with patriarchal views took Indigenous women as slaves to men, leading to rape, violence and submission, according to Native Hope.

As of 2021, Albuquerque and Gallup had among the highest numbers of MMIP in the United States, according to a report by the New Mexico Indian Affairs Department. Native American women in New Mexico experienced the highest rate of homicide among all racial and ethnic groups at the time of the report.

Primary factors that have perpetuated the crisis include poor handling by law enforcement and the enactment of federal laws on tribal jurisdictions. Congress limited jurisdictional authority to the federal government by enacting laws like the Major Crimes Act of 1885, which granted jurisdiction to federal courts – as opposed to tribes – for certain crimes, according to a 2020 report by the New Mexico Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Relatives Task Force.

Deiandra Reid is the land and body violence coordinator at the Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women. Reid’s sister Tiffany went missing in Shiprock in 2004 at the age of 16, according to Reid.

Reid works directly with families who have missing relatives and helps them navigate through the barriers she came across when her sister went missing, she said.

“I want to be able to help the families who are experiencing MMIP to have a better outcome for their loved one,” Reid said.

In March, the CSVANW launched a new law enforcement training program that uses a trauma-informed approach, according to Reid.

The way law enforcement handles missing person cases is not trauma-informed and is often unethical, she said.

“A lot of the time, law enforcement will place judgment on the family member rather than trying to understand that this is another human being who has a family,” Reid said.

When Reid’s family first spoke to law enforcement the day her sister went missing, they were told to wait 72 hours before they could file a police report because police believed she had run away, according to Reid.

Reid recently spoke to a member of a family from Shiprock whose brother went missing two years ago. His skull was recovered last year. Earlier this month, law enforcement returned to where the skull was found to search for additional evidence for the case, Reid said.

Get content from The Daily Lobo delivered to your inbox

After law enforcement officers finished the search, one of them asked the sister if just finding the skull would be acceptable, Reid said.

“She was so upset. And she told him, ‘If that was your family member, would you be okay with just a skull?’ And he was like, ‘No, I’d probably keep looking.’ And she was like, ‘Well, there's your (expletive) answer,’” Reid said, citing this as one example of law enforcement not being trauma-informed.

In 2017, the Urban Indian Health Institute conducted a study to investigate the MMIP crisis in 71 U.S. cities. The findings showed similar law enforcement experiences among multiple families who had missing relatives and long-standing complaints about failed responses from law enforcement agencies.

In 1956, Walcie Rae Downing, a mother of five, went missing at age 32 in Gallup. In 2016, author and historian Marilyn Hudson spoke with one of Downing’s family members.

“I had been touched, in my own research of other unsolved (cases), at how these women were so often ignored by police, forgotten by the public, and killers were allowed to go on to live their own life without consequence to their crimes,” Hudson wrote in a statement to the Daily Lobo.

Hudson recalled the family’s desperation to find closure.

“Their heartache at not knowing the fate of the woman they loved was heartbreaking,” Hudson wrote.

Reid shares a similar sentiment with her sister’s case.

“Good or bad, as long as she's home where she belongs. All I want is just that closure,” Reid said.

Tiffany loved to sing and write songs and poetry, Reid said.

“She would record herself and then she'd rewind it back and listen and re-sing it over so I could just hear her pushing the buttons in the other room,” Reid said.

Reid said Tiffany wanted to become a veterinarian because she loves animals and always tried to rescue them.

In addition to colonialism and ambiguous prosecution laws surrounding MMIP cases, natural resource exploitation is directly linked with the crisis.

The influx of mostly white males in poor working conditions in rural and predominantly Indigenous communities has caused “increased rates of violence, sexual assault, sexually transmitted diseases, prostitution, sex trafficking, and an increased presence of illicit drugs,” according to Joseph’s study.

At fracking sites, people come from different parts of the country to set up camp for employees, Reid said. She refers to these sites as “man camps.”

“These men from different places come out into the communities, and then they start victimizing the women and the girls within that community. Especially because I know New Mexico had a big oil boom a few years ago, and there were man camps everywhere,” Reid said.

This year, New Mexico Attorney General Raúl Torrez launched a public, online MMIP portal that shows active MMIP cases across the state. The database allows people to report and search for missing persons, including the cases of Reid and Downing.

“Sometimes people call it an epidemic, which doesn't make any sense to me, because this has been ongoing since the settlers came. And it's a crisis. It's a crisis that has started way back and it's still going on today,” Reid said. “And there is still very little being done about it.”

Paloma Chapa is the multimedia editor for the Daily Lobo. She can be reached at multimedia@dailylobo.com or on Twitter @paloma_chapa88

Paloma Chapa is the multimedia editor for the Daily Lobo. She can be reached at multimedia@dailylobo.com or on Twitter @paloma_chapa88