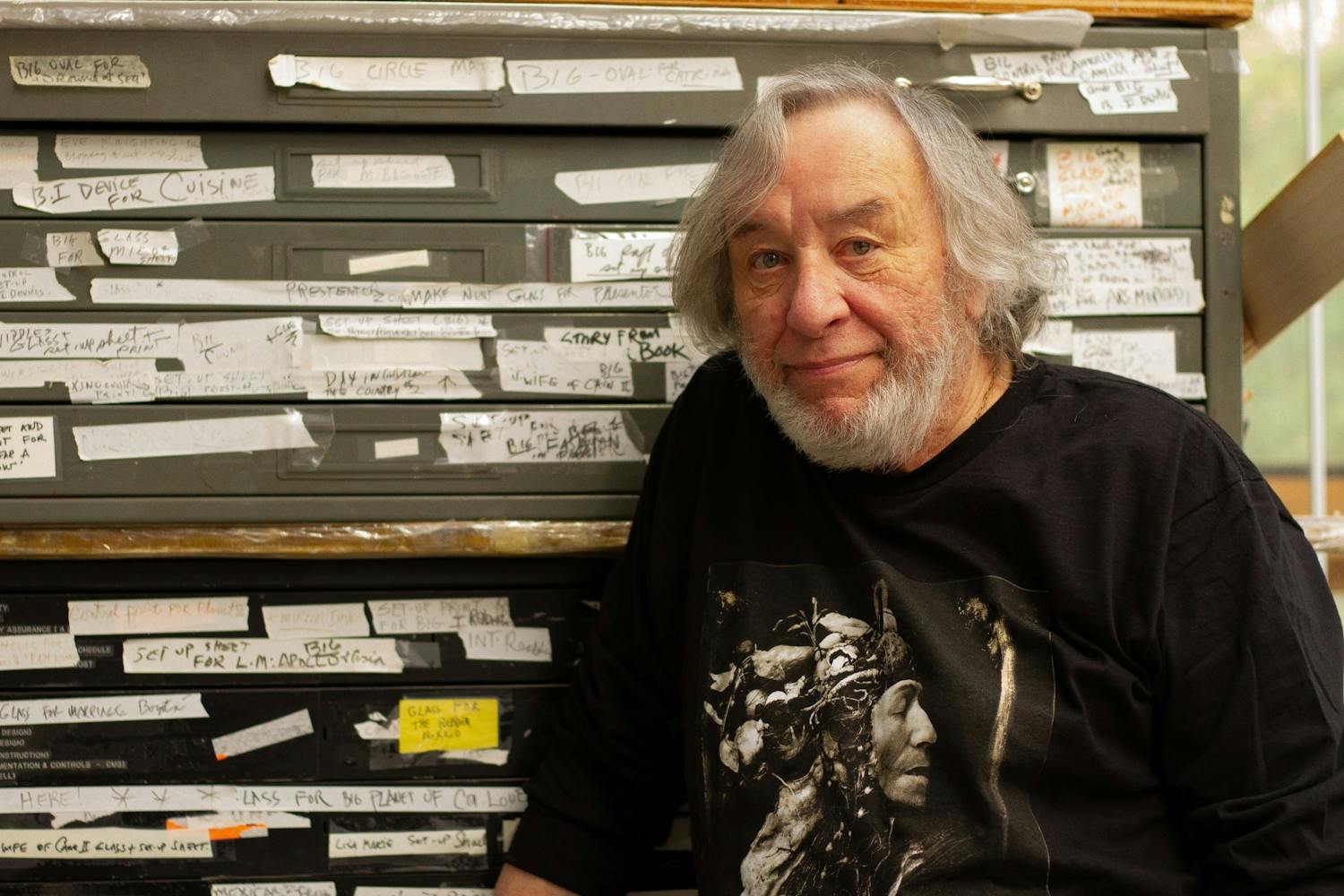

Joel-Peter Witkin is a University of New Mexico graduate with a prolific profession as a photographer of taboo subjects.

Witkin is known primarily for his ornately composed photographs of subjects ranging from socially outcast figures to deceased persons or body parts. One of Witkin’s most well-known pieces is “Le Baiser,” an image of a severed and halved head whose pieces have been faced toward one another in an apparent kiss.

Such subject matter has led Witkin to face his fair share of critical lambasting, with a 1993 article in the New York Times claiming his “prettified and pretentious images do little to illuminate the issues of life and death they raise.” A later profile in the Seattle Times noted his work had been deemed “the snuff film of the art world.”

Despite the criticism, Witkin rejects the notion that his work is overly morbid.

"I don't think it's macabre, I think it's the way my vision is — and it may seem macabre to people, or to have a dark factor, but it's the way I perceive reality. I think it's positive,” Witkin said.

Witkin described how his interest in photography started at a young age.

At 16, he received a camera from his father and began shooting. In 1961, a 22-year-old Witkin enlisted in the Army, where he served for three years as a photographer.

Following this stint, Witkin studied sculpture and poetry, receiving a bachelor of fine arts from Cooper Union in New York City, where Witkin originally hails. A recipient of the G.I. Bill, a fund that assists qualifying veterans with college and training costs, Witkin continued his graduate studies in photography at UNM, where he took inspiration from fellow local photographers Van Deren Coke, Wayne Rod Lazorik, Anne Noggle and Betty Hahn.

Witkin previously visited New Mexico as an army specialist stationed in Texas and said he felt something special and inexplicable in the state.

"I knew I had to be here. (There were) many, many factors,” Witkin said. “It was something I felt was in the history of my life ... I had to be here.”

Cynthia Bency-Witkin, Witkin’s wife, met him in 1976 as a fellow UNM student. Raised in Española, Bency-Witkin said she initially disliked New Mexico as well as UNM, which was the only local school her family could afford to send her to at the time.

“When I was young, I wanted nothing more than to leave. I felt like the big world was out there, and I just wanted to explore,” Bency-Witkin said.

Get content from The Daily Lobo delivered to your inbox

However, as Witkin’s photography continued to gain traction, the couple quickly realized they could do all of the photographic work necessary by staying local, and thus opted out of moving to larger cities like New York or San Francisco.

“The quality of life is fantastic. At the time, it felt like Albuquerque was the center of the world,” Bency-Witkin said. “I think our quality of life really flourished because we were able to live in New Mexico — to be able to have the land, the space.”

The couple attribute both New Mexico and UNM to Witkin’s ability to work so freely.

"Sara Raynolds was where the darkrooms were, and Joel used that darkroom like crazy, night and day,” Bency-Witkin said. “So finally, they were going to renovate Sara Raynolds, and they were saying ‘You have to leave, Joel, you have to leave.’ He'd already gotten his MFA, but he held on (to the University) until the very end.”

Referring to works such as “Art Deco Lamp” and “Abundance,” both of which showcase people with physical disabilities in striking and elaborate compositions, Bency-Witkin talked about her husband’s displays of people that are so often maligned or outcast.

“We all hope that we’re a unique person, that we have something to offer. If you're really not the norm in society, then it's harder. For the first time, many of these people were asked to be who they really were,” Bency-Witkin said. “A lot of these people became our friends.”

Though Witkin’s love of art and expression is still clearly visible, Witkin said he isn’t currently active in his work, having made his last print in late 2019.

“I'm retired. The work is very well-organized — I put my forty, fifty years in. Basically, I don’t have the energy to do it,” Witkin said in reference to the oft-laborious process of composing photographs and making large prints. “I've had it. I don't have that energy ... The best years of my life I put in.”

Witkin said his worldview on taboo and graphic material has never changed, even though modern artistic perceptions deem it more socially acceptable now.

“I've never accommodated anything. That was my vision, that’s how I saw the world, that’s what I did. And that’s the way it should be — art comes from the soul, the spirit, and it doesnt come from anywhere else,” Witkin said. “It can’t be adaptive. It was shocking to a lot of people, but I can’t help that.”

Liberty Stalnaker is a freelance reporter at the Daily Lobo. She can be contacted at culture@dailylobo.com or on Twitter @DailyLobo