Not only is the Farris Engineering building one of the newer buildings at the University of New Mexico, but it is also one of the deadliest buildings — for birds.

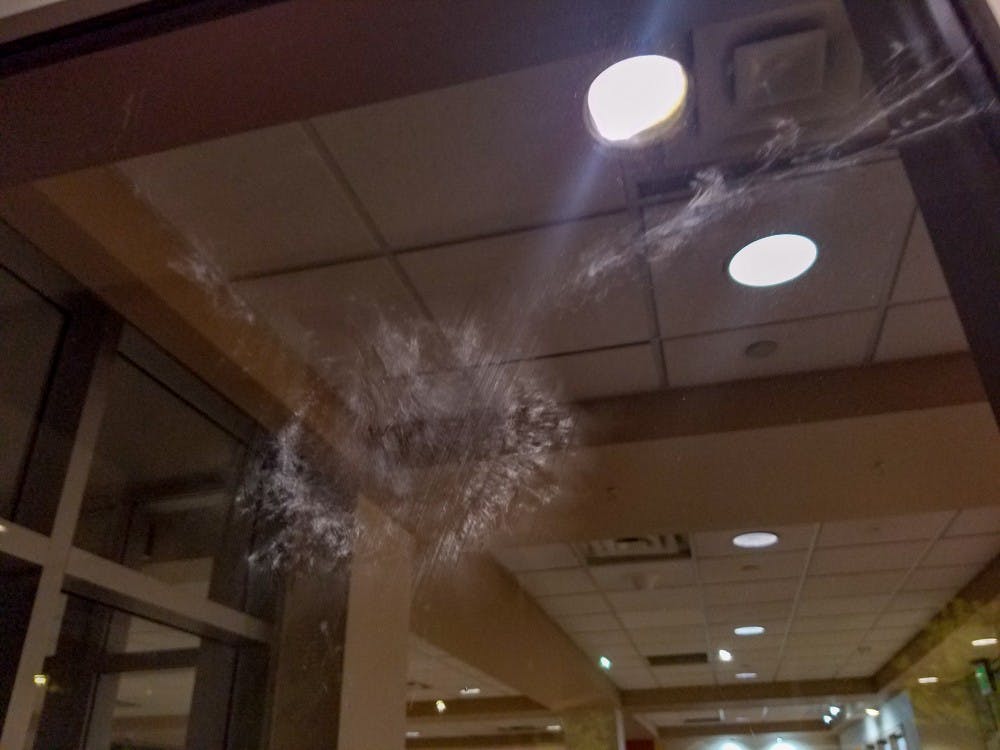

It stands erect against a blue sky, massive windows providing camouflage for an open ambush. Smudges on the reflective glass detail individual feathers of a wing and some bear the imprint of a beak, almost like a gravestone bearing their memory after hitting the glass.

Window strikes are not a new concept to the University. Data collected from Museum of Southwest Biology (MSB) researchers dates back to 1965 — the first entry marked the death of a ruby-crowned kinglet. Over the course of 53 years, more than 60 bird deaths have been recorded on campus. However, there is an issue with the data set — it is incomplete and sporadic.

Two MSB faculty and one former UNM student of biology and psychology, Danica Simmons, are trying to change that. Their combined efforts during the 2018 fall semester recorded 27 bird fatalities on campus, but Simmons said this data can be under-counted.

“There are definitely more (dead) birds than what I got,” Simmons said.

Simmons said for three-months, two days a week, she arrived and started her research on the 769-acre campus by 6:30 a.m., and usually finish by 9 a.m. because her subjects are most active in the morning. She said she tried to tour at least 14 buildings looking for dead birds and noting for changes in their habitat like new nests.

“It’s incredibly limited because I try to do a thorough inspection of the buildings, but I’m limited on time and also energy,” Simmons said, adding that feral cats in the area tamper with her research subjects.

“If there was a bird or not, I don’t know — something could have taken off with it,” Simmons said.

Window strikes don’t discriminate against their victims — of the more than 20 birds Simmons recorded in the Artcos database, 14 of those were from different species of birds like dark-eyed juncos, black-chinned hummingbirds, rock pigeons and more.

This is reflective of the diversity of birds that die from window strikes in the overall Artcos data set, like a greater roadrunner that died in 2012, a western screech owl that died in 2009 or a sharp-shinned hawk that died in 1988.

Simmons said most of the dead birds she came across in her 2018 study were warblers that crashed into buildings while migrating at night. She added that most of the birds she came across share a common trait — they’re young.

Simmons said young birds’ inexperience with migrating and undeveloped senses can lead to window strikes.

Get content from The Daily Lobo delivered to your inbox

“It’s really depressing because it’s their first and their last migration for a lot of them — you can tell because of some of their molts and everything that’s not fully developed,” Simmons said.

Simmons said the hot spots for window strikes occur at the Farris Engineering Center and at George Pearl Hall because of their large and uninterrupted window design. But, Simmons said, there are many spots on campus that are bird friendly like the area south of Zimmerman Library with a fountain and a broken-up window pattern and shaded area. Simmons said she stopped looking for dead birds around this area because of its low-risk.

Simmons said she suggests that large windowed buildings use decals or an ultraviolet filter over the glass to break up the never-ending sky reflection.

“I really care about birds and this is a kind of needless death,” Simmons said.

Anthony Jackson is photo editor for the Daily Lobo. He can be contacted by email at photoeditor@dailylobo.com or on Twitter @TonyAnjackson.