Much has been said at varying levels about the pay gap between different genders and ethnicities in certain industries, but when factoring in rank and field of study, women and minority faculty are almost paid equally to men at UNM.

However, according to a report analyzing base pay of faculty from the Office of the Provost, men are more likely to be promoted to full professorships, while salaries for women and minorities become less “competitive over time.”

In 2007, the UNM Economics Department conducted an analysis of faculty compensation for the Office of the Provost and found that — on average, without looking at rank and field of study — women faculty earned 87 percent compared to the salaries of white, non-Hispanic men.

Yet, when rank and field of study are taken into account, the gap becomes much smaller at 1.7 percent.

The 2007 study reported, “Human capital and department affiliation account for most – but not all – of these raw gaps. After controlling human capital and department affiliation, a gender gap of 1.7 percent remains, and a 4.4 percent gap opens for African American faculty at the University level.”

In addition, the 2016 Provost’s report “contracted the Bureau of Business and Economic Research to assess” pay gaps based on race and gender.

The research found that, when faculty salaries are averaged across the board without looking at rank and field of study, women faculty members at UNM make about 15 percent less than men.

Meanwhile, when rank and field of study are included, “women faculty of any race” have salaries that are .7 percent higher than white, non-Hispanic males in 2016.

Carol Parker, UNM’s senior vice provost and author of the preliminary report cited above, said that looking at salary averages without taking into account other variables can be misleading.

When averages are examined — without accounting for rank, field of study and overall head count — it becomes very hard to measure progress and understand what factors are causing discrepancies.

Moreover, having accurate data is critical for making the right moves forward, Parker said.

“Holding consistent factors, such as academic field and years since terminal degree, salaries of female assistant and associate professors are 1.2 percent higher than those of white, non-Hispanic males of the same rank, while salaries of female full professors are 1.4 percent lower than those of more numerous white, non-Hispanic males,” the 2016 report states.

Get content from The Daily Lobo delivered to your inbox

Parker said the data from last year suggests that women and minority faculty are not promoted as often as white male faculty, and UNM may need to look more closely at how minorities and women are promoted to see if a double standard exists.

According to the 2016 report, male professors “are more likely than female faculty to have ranks of full or distinguished professor (39 percent male vs. 22 percent female), reflecting a legacy of the 1980s and earlier.”

The 2016 report noted that a trend of males being overrepresented at the full professor level has begun to reverse.

“One of the problems we know we need to address is the fact that if somebody starts out at an uncompetitive rate, it becomes very difficult to move them up over time because of our fiscal challenges,” Parker said.

The data from the Provost’s report makes it clear that it cannot be assumed that minority professors always make less than their white male counterparts.

In fact, the compensation picture is very complex, containing many variables, and averages do not accurately portray faculty compensation discrepancies.

For instance, according to the 2016 report, at all ranks the “very small number of black faculty” are compensated between 1.6 and 8.1 percent more than white male faculty, yet Hispanic males and females make between 1.2 and 4.7 percent less than white men.

Moreover, “Best illustrating the complexity of these patterns, salaries of female Native American faculty are between 0.7 percent and 3.2 percent lower than white, non-Hispanic males, depending on rank,” the report states, while salaries of male Native American faculty are about one percent higher than the same group.

Earnings of both female and minority faculty are more equal for lower ranks like assistant and associate positions as well.

For the last several years UNM has worked on further closing these wage gaps between gender and race, Parker said.

UNM, as of last year, allocated $600,000, in part to compensate faculty salaries that were below national averages. Some of that money went directly to closing inconsistencies based on gender and race.

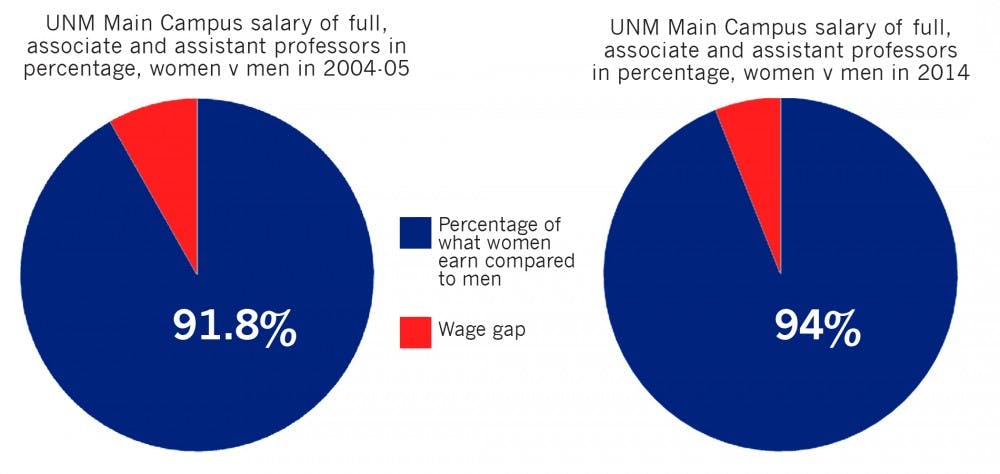

“Our preliminary analysis of the adjustments showed that proportionately more of the adjustments were directed to women and minorities in the senior ranks, as was intended,” Parker said. “This was the third assessment of Main Campus faculty compensation rates within the last 10 years. Each time we make these assessments we see the gaps getting smaller – and they are now very small – but more work lies ahead.”

To Parker, understanding faculty salaries at UNM requires an in-depth look at the individual faculty member in relation to rank, department, academic career and other factors.

This new allocation of money will help UNM officials better understand what is needed to decrease wage discrepancies, she said.

“We will assess the full impact of the most recent round of salary adjustments, down to the level of the departments, to measure their effectiveness at moving us closer to our compensation goals,” Parker said, adding that UNM plans to see if compensation policies might be outdated.

Eliza Lawler, a freshman biochemistry and foreign languages double major, said ze believed it is important for UNM to make sure there is as little of a wage gap as possible.

“As a student, it’s important that women faculty be paid equally, as they do the same work and should be compensated appropriately,” Lawler said. “Women and non-binary professors are equally capable as their male counterparts, and they each bring their unique skill set to the classroom, which would be impoverished if they were not there.”

Lawler said pay gaps could potentially discourage female professors to pursue a position in academia.

“As a non-binary person in a STEM major, I have noticed a distinct lack of women and non-binary people like me,” Lawler said. “It’s isolating to be one of a few. Pay gaps drive away female teachers, which furthers that sense of isolation.”

Jonathan Natvig is a news reporter for the Daily Lobo. He can be reached at news@dailylobo.com or on Twitter @Natvig99.