by Christopher Sanchez

Daily Lobo

After Sunday, Joy Johnson will leave Albuquerque for Oklahoma.

Four days later, she'll be in Dallas. A week later, it's Louisiana.

By December, she will have traveled to seven states in four months.

Get content from The Daily Lobo delivered to your inbox

As a carnival worker, she's had the same routine for 21 years, but she wouldn't want an office job.

"It's called confinement," she said, laughing. "I don't like confinement. It's like being in jail."

Johnson said there are many labels for her profession, but she despises the word "carny" the most.

White trash, an alcoholic or a drug addict, that's what a carny is, Johnson said.

Though some carnival workers fit that description, she took a different path, she said.

"You can take the one I'm on, or you can take the one a lot of these people are on - dope, drugs, alcohol," she said.

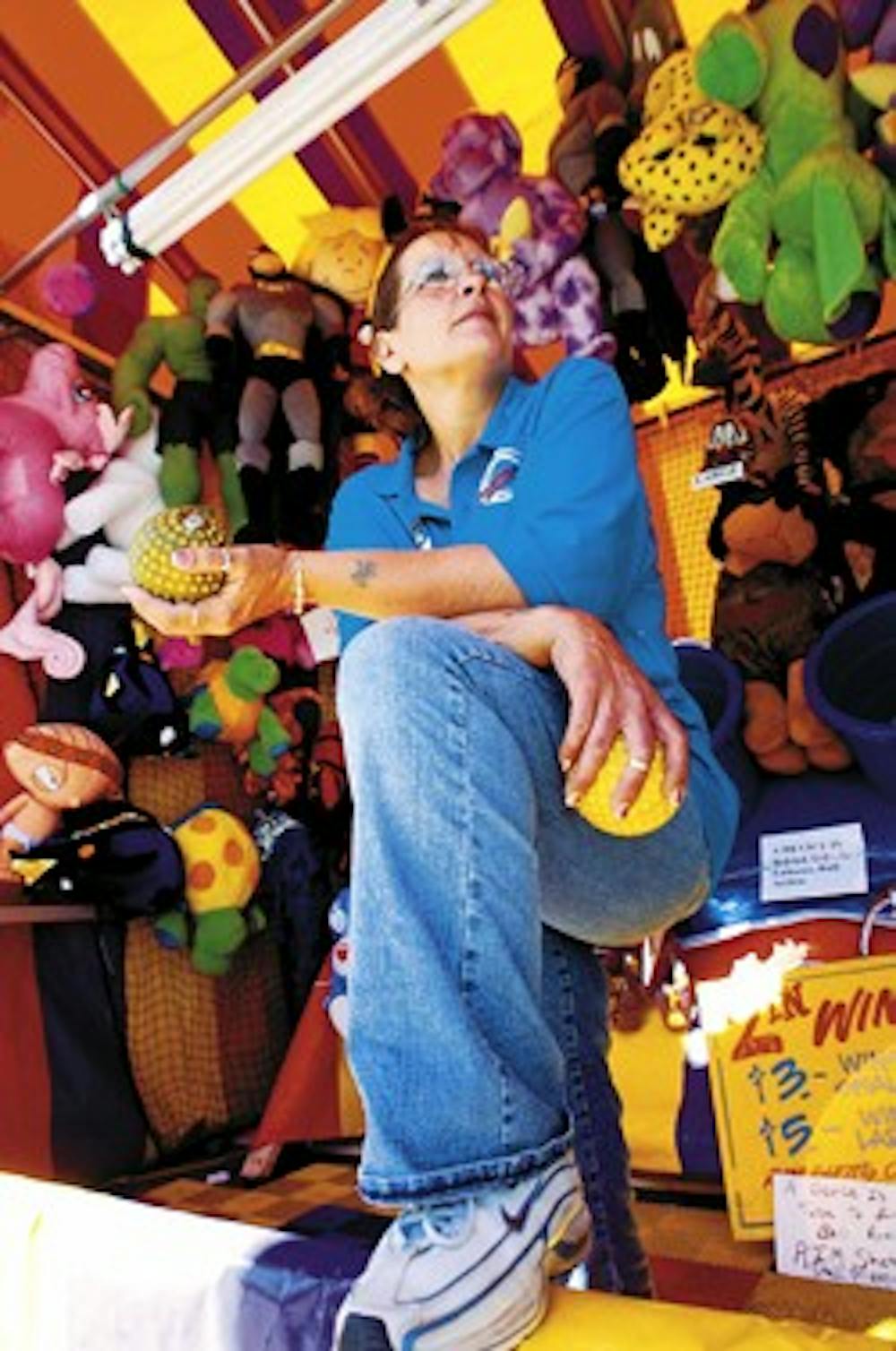

Johnson, 47, arrived in Albuquerque two weeks ago for the New Mexico State Fair. She runs a game booth called "Tubs," where a person lobs a softball into a bucket to win a prize.

It's not the traveling that keeps Johnson interested in her job, nor is it the new faces she encounters every day - it's the money, she said.

She makes 33 cents of every dollar spent at her booth. It might not seem like much, but after working almost 15 hours a day, it adds up, she said.

On a good year, she makes about $50,000.

"It depends on you, on how hard you work. A lot of these people don't want to come out here and work," she said. "You have to hustle."

Johnson said she lures customers to her booth by giving them a free game.

"You have to be a people person," she said. "You have to enjoy people. You have to enjoy life. Life is too short."

She then spotted two boys and singled one out.

"Here, honey. Come on over here to win," she said. "Let me give you a free one. Come here. Let me show you how easy it is to win."

The two boys continued walking without acknowledging her.

"I get a lot of them mad, but that's how you get them in sometimes," she said.

When Johnson finishes her shift, she explores the city and visits bars.

Johnson is living in a motel close to the fairgrounds.

There is housing on the grounds, but she doesn't like the chaotic environment that comes with living there, she said.

"It's just a lot of drama," she said. "A lot of fights, a lot of drinking, a lot of things I'm just not into."

Those living on the fairgrounds live in bunkhouses, which are small trailers with seven rooms.

Though carnival worker Daniel Roberts is living in a motel, he visits the bunkhouses every night to party and shoot dice.

"We all hoot and holler all night long," he said. "Last night, I didn't get to bed until three in the morning. We had a couple 30 packs."

Albuquerque resident Ed Ramkowsky said he views carnival workers as party animals.

"I don't know what it's like these days, but when I was younger, I remember them as travelers doing drugs, drinking booze and just partying," Ramkowsky said.

Albuquerque resident Trudy Porter disagrees. She said it's wrong to judge.

"It could be the kid from next door for all I know," said Porter, who was at the fair on Saturday. "They're just normal people."

Ramkowsky, who was also at the fair on Saturday, said he keeps an eye on the workers to make sure they don't harm his grandchildren.

"To me, they are carnies," he said. "They go from one state fair to the next. They don't have any roots."

Too many people label carnies, said Michael Quinney, a carnival worker.

"Everyone has their own idea of a carny," he said. "But there are a lot of them out here who have degrees in college and there are those with no teeth."

Being a carnival worker can help someone start a career, he said.

It's getting him one step closer to his dream - being a comedian.

Quinney said he jokes with people when they pass his water gun booth.

"If they don't want to play, you have a wise crack for them like, 'Oh, what, you don't play well with others? Are you afraid of water guns?' Something like that," he said.

After he finished his duty with the Navy, the 33-year-old became a carnival worker so he could

continue traveling.

He's been doing it for three years.

"I live to travel," he said. "I love to meet new people. It's something I've always liked to do. I'm a free spirit."

Quinney said he takes half the year off to relax.

Johnson takes two months off, but she leaves a carnival any time she isn't making money.

"When it's no good, you leave," she said. "If there's no money, I don't stay. It's just plain and simple."

As long as she is a good worker and doesn't steal from the company, she is always guaranteed a job.

It's all about a worker's reputation, she said.

"I can walk on to any show anywhere in the world and get a job," she said. "I called a man the other day. He doesn't even know me, but he knows my name. He knows where I'm from and what I'm about. He told me, 'Come

to Dallas.'"

For Cindy Ritch, 17, it's too risky to leave her post whenever she wants.

"If you leave, you won't have a job," she said. "The boss is really particular about that."

If she gets fired, she could lose her opportunity to attend college.

Ritch, who has been a carnival employee for a year, said she is saving money for college and wants to become a teacher.

She expects to make about $2,000 from the New Mexico State Fair.

The money doesn't come without hard work, she said.

If she is lucky, she will get a couple days off during her stay in Albuquerque. She works about 12 hours a day.

With so much time dedicated to work, Ritch said she doesn't have time for relationships.

"I've had one (boyfriend), but it was hard to keep one," she said. "He traveled. I traveled. It didn't work out."

During her year working at fairs, she has sold food and worked game booths.

At the state fair, she is working a game called "Splash Down," where a person inserts quarters into a machine to win money.

It's almost like a slot machine, she said.

"You get some people who stay here all day, spend all their money," she said.

Ritch said New Mexicans like to play that game.

Johnson said she has to work extra hard to get New Mexicans to play her game.

"They don't like to spend money," she said, laughing.

She had the same problem in North Carolina, where she was before coming to Albuquerque.

She said traveling can be depressing, because she doesn't get to see her two children. Her son is 21 and her daughter is 19 years old.

"But all it takes is a plane to see them," she said. "I can leave at any time, go see them and come back."

When her children were younger, it was difficult, she said. They would stay at their grandmother's home or travel with her.

Johnson has held other jobs, but she will retire as a carnival employee through a private firm in three years, she said.

Just as Johnson is planning her retirement, Roberts is getting started in the business.

He started working at carnivals a week ago. He said it's the best job he has ever held.

He became a carnival worker because all his friends were doing it, he said.

Roberts, 21, said he is a natural traveler. He ran away from home for the first time when he was 15.

Roberts said he keeps in contact with his family by telephone.

"I'll call once a week and tell them I'm doing all right," he said. "That's all they care about. They want to make sure I'm not getting into trouble."

It's not hard to get in trouble, Roberts said. He has seen carnival workers get arrested for possession of drugs.

Those are the bad carnies, he said.

"A bad carny is people who like to stay up and stay up and stay up and never go to sleep, go on a rampage, hollering, throwing stuff," he said.

The rest are human beings, he said.

"We kick back, but we're just like everybody else," he said. "We sit there and gather up in the bunkhouses at night and drink a couple beers, sit back, relax, chill, get ready for the next day. Besides that, we're normal."