Nestled far back on the University of New Mexico’s North Campus is a building dedicated to trying to cure what is arguably one of the most formidable conditions — its most common form: dementia and Alzheimer's Disease.

UNM’s effort to better understand, diagnose and treat dementia is embodied by the UNM Memory & Aging Center. Operations at the center began in 2015, but an open house was held on Dec. 6 to showcase its progress and research.

Dementia is a condition that results in the deterioration of cognitive function, including a decline in memory, reason and the ability to learn. Alzheimer’s is a neurodegenerative disease that has no cure, according to the Centers for Disease and Prevention Control.

Currently, there are an estimated 38,000 New Mexicans and more than five million Americans who are diagnosed with Alzheimer’s — by 2050, the number of Americans with the condition is expected to rise to 16 million, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

New Mexico follows the footsteps of 31 other states by having this type of center, but UNM’s center is the first of its kind in the Mountain West region (which includes New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Nevada and Idaho) or in the Upper Plains states.

The center houses a compilation of doctors specialized in internal medicine, psychiatry and neurology all working together to collaborate on research and treatment.

During the open house, speakers such as Memory & Aging Center Director Dr. Gary Rosenberg, Gary L. J. Girón — the executive director of the Alzheimer’s Association New Mexico Chapter — and others spoke about the center’s accomplishments thus far.

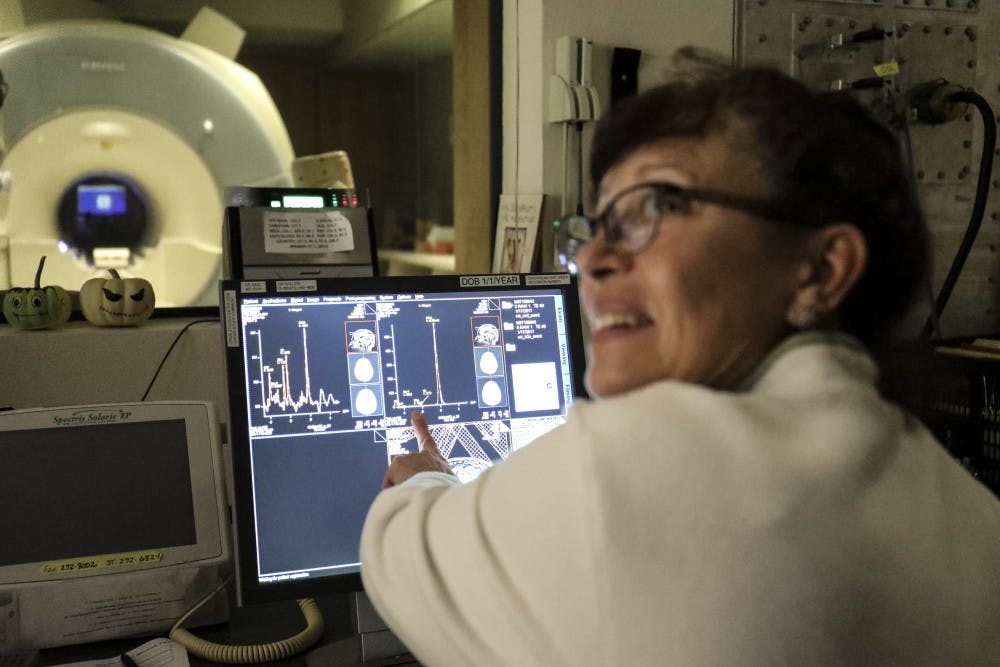

One topic the center is currently working on is the effect of nicotine patches on patients who exhibit difficulty with their memory. Dr. Janice Knoefel, the clinical director at the center and previous Chair of the Department of Neurology at UNM, spoke about the trial.

Knoefel said the patients involved in the study are not diagnosed with dementia or Alzheimer's, but they have what is called “subjective memory complaints,” meaning, through their own self-examination they notice a decline in their memory. She said she takes these complaints seriously and considers those patients for the clinical trial.

Because the patients do not rank high enough to be diagnosed with dementia, they are instead said to have mild cognitive impairment, Knoefel said.

A recent study said that 80 percent of people who suffer from mild cognitive impairment are going to develop dementia, Alzheimer’s or a similar disease, she said.

People most commonly associate nicotine with tobacco and smoking, which are proved to have negative effects on health. However, the hopes of using nicotine to combat memory deterioration comes from its ability to act as a stimulant.

Get content from The Daily Lobo delivered to your inbox

“Nicotine is not necessarily a bad thing, but how we get it is a bad thing,” she said. “Smoking’s no good, we know that.”

Due to nicotine’s ability to “wake up” someone’s attention mechanisms, Knoefel said some people consider it to be a cognitive enhancer.

What makes the chemical useful are receptors, named Nicotinic, in the brain that recognize nicotine and convert it, therefore increasing alertness and attention — otherwise nicotine would be an powerless substance, Knoefel said.

The study aims to prescribe people with early memory problems a nicotine patch and then monitor if the “flood” of medication stimulates the wakefulness and the attention mechanisms of the patient enough to help with their memory problems, Knoefel said.

The study began by prescribing low-dose nicotine patches and slowly graduating patients to higher doses to avoid becoming sick, she said.

Knoefel said the center would like to eventually try the treatment on Alzheimer's patients, but they must first “backup” the treatment process and detection to catch the disease early because after significant damage is done, it might be irreversible.

“It’s kind of like the philosophy for treatment of Alzheimer’s,” she said. “You have to have something to work with.”

The center is funded on a five-year grant, paying $1 million per year from the National Institutes of Health, which still has three years remaining, Rosenberg said.

Without donors, he said the sustainability of the center is the next challenge they must face.

Chris Chaffin, the media director for the Alzheimer's Association New Mexico Chapter, said the group fully supports the center’s endeavors.

He said that before the center opened, it was difficult to point people suffering from Alzheimer’s and their families to a good place with the correct resources, but now that has changed.

“It’s really changing the dynamic,” he said. “It’s finally like there is something — (the center) is a light house, it’s a beacon, it’s something that bares hope.”

Madison Spratto is a news editor at the Daily Lobo. She can be contacted at news@dailylobo.com or on Twitter @Madi_Spratto.